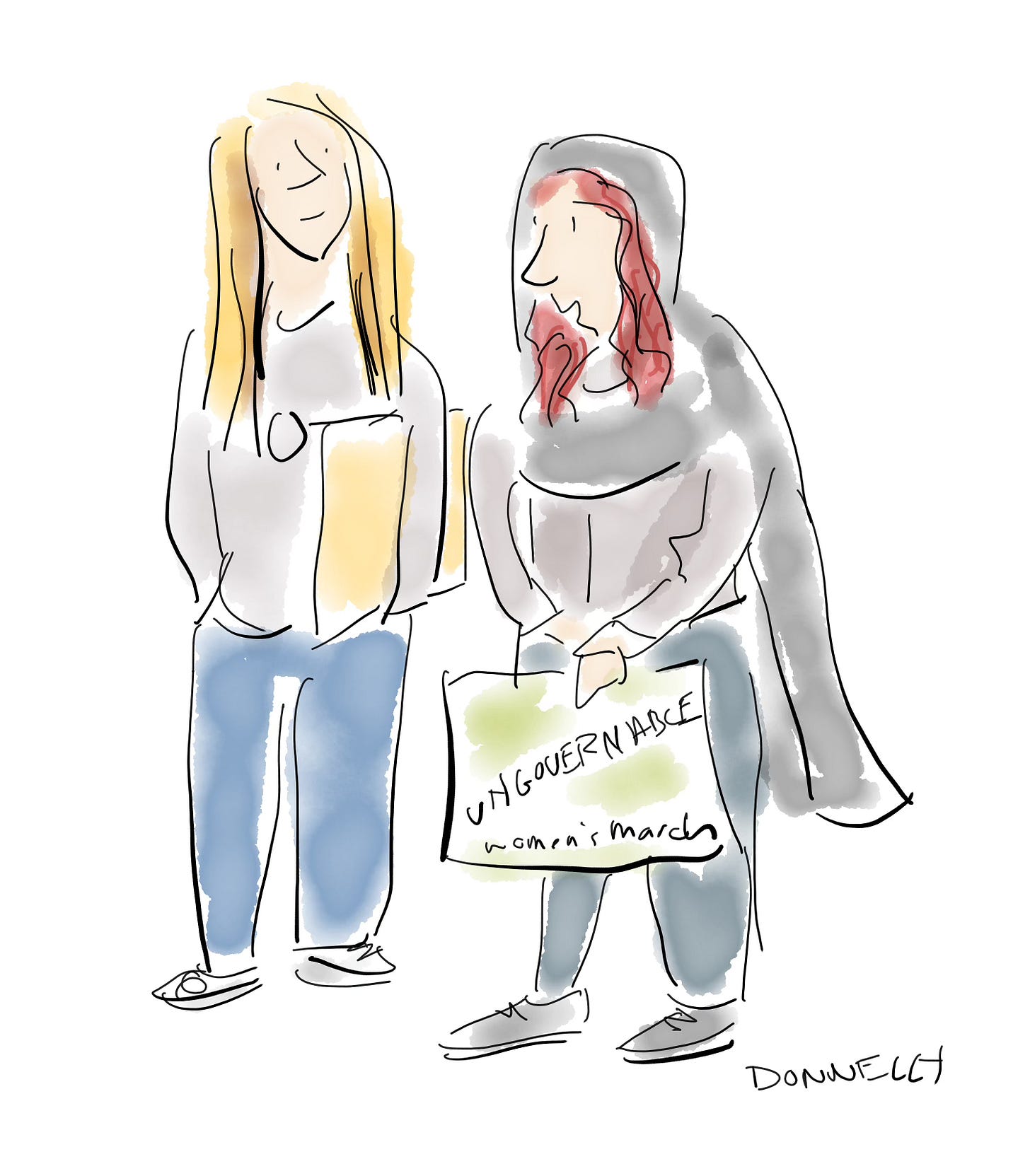

Just a short walk from the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC, I met a 15-year-old girl named Tegan on January 18. She had traveled two and a half hours from a small town in Pennsylvania and was among the thousands who’d joined the “People’s March” ahead of Donald Trump’s inauguration. We talked for about 10 minutes while New Yorker cartoonist

drew her and her friend. The conversation left me unsettled.I wasn't surprised that Tegan was disappointed with her Republican father or that she was upset that the Supreme Court, stacked with Trump-appointed judges, had ruled to end bodily autonomy and reproductive rights for many women in the United States. Everyone I talked to at the march said they wanted freedom from policies that hinder one’s right to health and humanity. People were calling for an end to the war in Gaza, as well as demanding racial equality, LGBTQIA protections and checks on democratic backsliding here in the United States.

I was stunned, naively, that Tegan didn’t express hope for a better world. When I asked what kind of future she’d like to imagine and build, her answer was bleak: “I can't really think of a future that I want to build because I have a high feeling that we won't be able to build it because women don't really get much of a say. I have a feeling if this is how, like, 12,000 years of us have been, I don't think a change is going to happen in my lifetime.”

I understand the sentiment, particularly for kids growing up in a polycrisis. No other generation has had so many interconnected, massive problems amplifying each other, making them harder to resolve. This era in history cannot be compared to the Cvil War or to World War II, which are often what Americans point to when trying to suggest it’s been bad before.

The current crises in climate, democracy, mental health, gun violence and more are not just happening simultaneously, they’re feeding into and exacerbating one another. So, yes, I can appreciate it feels like a change cannot happen in our lifetime because, holy hell, there’s a lot of repair — and reimagining — we need to do.

But I’m going to offer a different perspective because I personally need a little light at the end of the tunnel, and there was plenty of light at the march. Since Homo sapiens began evolving between 800,000 and 300,000 years ago, we have faced existential threats at every stage of our development. And every single person has faced a challenge that at some point has felt insurmountable. Nevertheless, we persisted.

We persist because two things can be true at once. Both doom and hope can exist. We can love and hate the same person. Insistence on only one factor being true is what gets us stuck. Binaries are where danger lies. Dialectics are where possibility emerges.

Dialectics is the idea that reality is not static — opposing forces interact and evolve over time. The challenge of being human is learning to live with “both/and,” instead of “either/or.” In dialectical behavior therapy, thinking, feeling or acting in extremes is understood as attempts to avoid the pain of emotion. But this can be dangerous for our own health and others’, threatening our very survival. America’s suicide crisis is a testimony of this. By learning to tolerate emotion, to even appreciate the insight that it brings, people can opt out of escapist behaviors that contribute to the polycrisis we’re in — behaviors such as drinking, doing drugs and blaming others — people and nations — for the problems we’re unsure of how to face at home.

The hazard of getting stuck in the gloom and doom is that there is nothing to do but fear and suffer and experience all the side effects of hopelessness, which prevent us from doing the things that are necessary to change. The hazard of getting stuck in a “this will pass” or “it’s not so bad” mentality is that we could miss a real danger signal that something is seriously wrong. There needs to be a synthesis in the middle.

Taking good care of one’s self — especially in a time of peril — means sometimes accepting what we cannot change in this moment, and not shutting down completely or doing things that make it worse. It also means not getting totally comfortable with dysfunction.

I’ll share an example from my own life. I covered the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol four years ago and suffered serious post-traumatic stress that made my brain and body perceive danger with every unexpected noise and motion. I wanted to keep covering social movements and do basic things like go jogging alone in Rock Creek Park, but my nervous system would panic if I even saw a flash of red that might be a MAGA hat. I didn’t think I’d ever feel safe again, and the world felt pretty doomed. I had to take a break from reporting on what I wanted to cover. I had to ask friends to go with me on walks. And I had to not accept that trauma would limit the rest of my life. I did massive amounts of therapy and moved through tremendous pain and, with it, I began to feel better, stronger, more hopeful than I’ve ever been.

Practicing acceptance, grieving, and then finding concrete ways to innovate, to change or to organize enables us to face challenges and solve real problems within the constraints of the world as it is now. I returned to covering social movements on Saturday. As I wove through the crowd with Liza, my anxiety grew, worried we’d get trapped or that someone might attack the peaceful march. I told Liza that I needed more breathing room, and we found ways to observe without being crushed.

In an open space, I met a group of women who’d traveled from South Carolina to draw on the strengths of others so they could inject the power into their movements back home. They said they work with communities who face great injustice, and they wanted inspiration and support from the march to keep up the fight. The women, in their 30s, 40s and 50s, had a sense of humor in their colorful costumes and in their signs, one of which read, “Did you buy the planet dinner before you fucked it?”

I asked one of the women how being at a march like this helps her mental health. She told me that being in community is an antidote to addiction. How? She said addiction makes you isolate in fear and pain. Being with others helps you see and feel what’s possible beyond it.

It turns out this wisdom is timeless and, even at 15, Tegan has it. When I asked her if there are small areas where she feels a bit more in control — even when the world is overwhelming — she turned and reached for her friend. “For me, when I'm stressed out,” she said, “being with another person totally helps.”

I want to thank , , and so many others for tuning into my first live video with . The cell reception at the march was a.w.f.u.l because of all the people, and we were experimenting on the fly. The fact that you believed in us, or were curious enough about our approach, to tune in is heartening. “Being with another person totally helps.” I’m planning to pop down to the Inauguration on Monday, despite the cold, and I’m crossing fingers that the A/V might be a little better. Liza won’t be joining as planned, but I’ll have plenty to report, and I’m looking forward to sharing it with you.

New to Invisible Threads? These might interest you…

A Big Lie Fueled Jan. 6 because America can’t face the pain of truth

Renovating a life with foundational issues

The daily antidote to the merchants of bad

Share this post