What the Khmer Rouge can teach the U.S. about tyranny

The 50th anniversary of the Cambodian genocide is a warning for America: Unhealed trauma can become the foundation for authoritarianism.

Publisher’s Note: This essay is intended to empower you with information, to ground you in history and to offer hope for the future. When we understand how harm spreads, we’re better able to stop it and choose a different path. An action guide is at the bottom of this essay. Please spend time with it and pass it on — like, share, restack.

Visibility is what keeps this work in motion.

In the ruins of war, even false promises can feel like salvation.

Cambodians know this well. Fifty years ago, they were desperate for stability after a U.S.-backed coup led to a civil war that dragged the country into the larger Vietnam conflict. American fighter pilots had dropped an estimated 500,000 tons of bombs on the country, killing as many as 150,000 people.

Cambodians were exhausted, hungry and afraid.

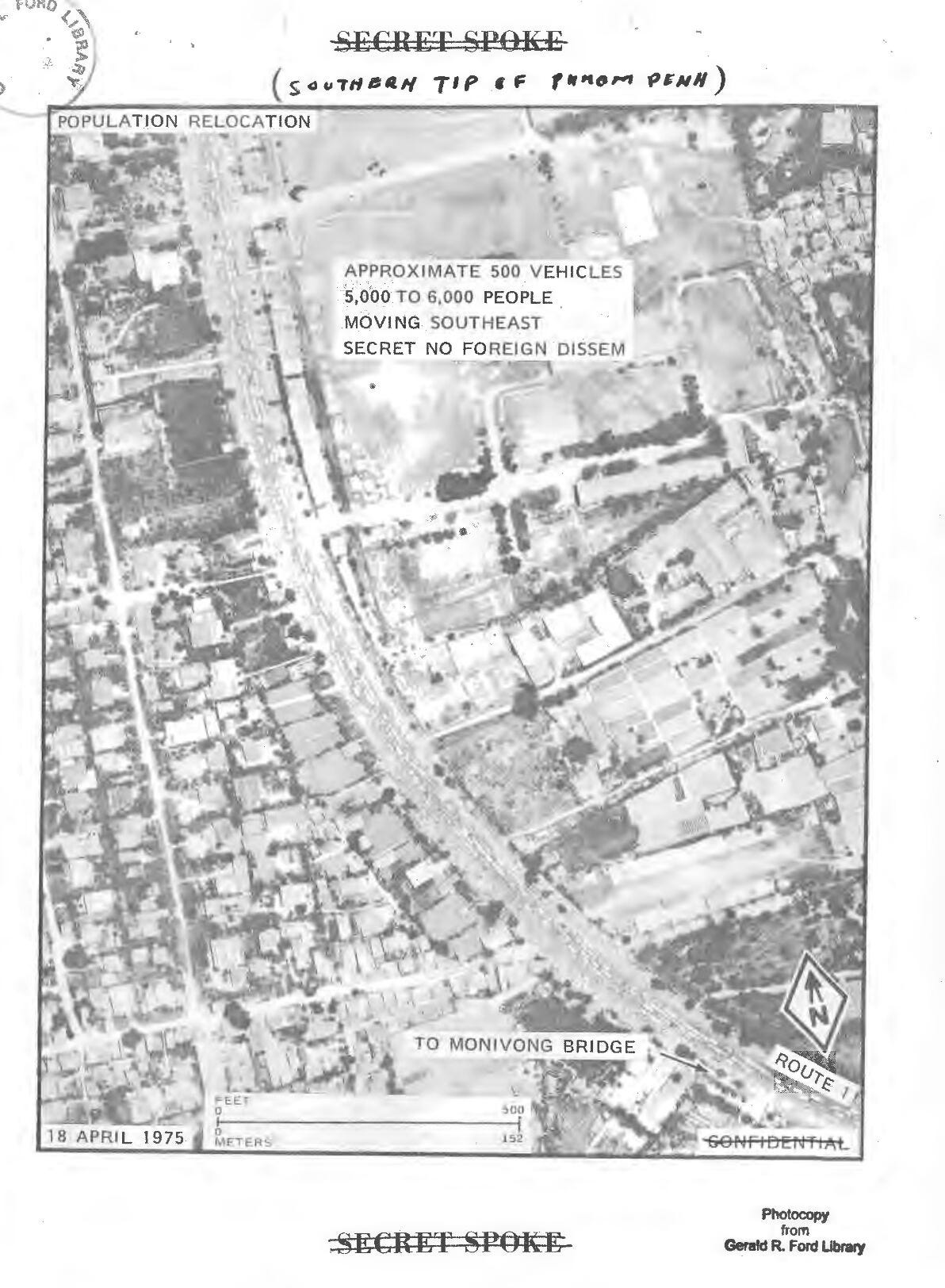

So when Khmer Rouge rebels seized the capital on April 17, 1975, people celebrated. They thought the scrappy communist soldiers who beat the American-backed government would make Cambodia great again. Before the conflicts, the country was rich with history and culture — ancient temples, film, literature and a vibrant music scene. People wanted that life back, and they thought the Khmer Rouge wanted the same.

They couldn’t have been more wrong.

“Even after our warmest welcome, the first word from the Khmer Rouge was a lie wrapped around a deep anger and hatred of the kind of society they felt Cambodia was becoming,” Teeda Butt Mam wrote in Children of Cambodia’s Killing Fields, an anthology compiled by Dith Pran.

Influenced by China’s Mao Zedong, the Khmer Rouge were both brutal and calculating. They claimed Americans were going to bomb the cities, sparking panic that made millions of people comply with orders to leave their homes and even hospitals to take shelter in rural camps. The fear-mongering worked because most Cambodians couldn’t fathom that their liberators had come to destroy them. “They risked their own lives and gave up their families for “justice’ and ‘equality,’” Teeda Butt Mam said. “How could these worms have come out of our own skin?”

Once displaced from their homes, Teeda Butt Mam recalled, “They separated us from our friends and neighbors to keep us off balance, to prevent us from forming any alliance to stand up and win back our rights. They ripped off our homes and our possessions. They did this intentionally, without mercy.”

Then the killing started.

The men were targeted first. The Khmer Rouge then killed their families to avoid revenge. “They openly showed their intention to destroy the family structure that once held love, faith, comfort, happiness, and companionship,” Teeda Butt Mam wrote. “We were not allowed to cry or show any grief when they took away our loved ones.”

The Khmer Rouge said they would make Cambodia a self-sufficient, egalitarian society that grew its own food. People who could read, write and think were treated as threats. “City people” like government employees, doctors, lawyers and poets were worked to death, starved to death, clubbed to death by their fellow countrymen. “I became afraid of who I was,” Teeda Butt Mam said.

“They accomplished all of this by promoting and encouraging the "old" people, who were the villagers, the farmers, and the uneducated. They were the most violent and ignorant people, and the Khmer Rouge taught them to lead, manage, control, and destroy. These people took orders without question. The Khmer Rouge built animosity and jealousy into them so the killings could be justified,” according to Teeda Butt Mam. “They ordered us to attend meetings every night where we took turns finding fault with each other, intimidating those around us. We survived by becoming like them. We stole, we cheated, we lied, we hated ourselves and each other, and we trusted no one.”

“We survived by becoming like them. We stole, we cheated, we lied, we hated ourselves and each other, and we trusted no one.“

Between 1.5 million and 3 million Cambodians died between 1975 and 1979 in a state-sponsored genocide the world didn’t stop. The killers even held a seat at the United Nations. Infighting and paranoia ultimately weakened the Khmer Rouge, allowing Vietnamese forces informed by Khmer Rouge defectors to invade and topple the regime.

The international community hailed the fall of the Khmer Rouge as a moral triumph. They marked it as the end of horror and the beginning of healing. But that narrative was only partly true. Overlooked were the ways trauma calcifies when it’s politically inconvenient to face.

This is the lesson for America and the world.

Trauma is a biopsychosocial wound that disrupts the body’s stress response system, particularly the amygdala (fear center), hippocampus (memory and context) and prefrontal cortex (rational thinking and regulation). When trauma isn’t processed, the brain becomes more reactive and less reflective, and the nervous system stays on high alert (fight, flight, freeze or appease). People may develop a lower tolerance for ambiguity, conflict or vulnerability — all of which are crucial for democratic life and healing.

Unprocessed trauma often gets externalized. What internal wounds can’t be acknowledged and treated can be projected onto others — through blame, control or silencing. What’s not healed gets reenacted.

In the decades since the fall of the Khmer Rouge, Cambodia hasn’t fully healed — it has stabilized. And there's a difference. U.N.-backed war crimes tribunals were delayed for decades until the early 2000s, when I spent four years there as a reporter in Phnom Penh. Most perpetrators lived freely. Victims were told to move on. Hun Sen, a former Khmer Rouge soldier who helped Vietnam invade Cambodia, ultimately became the country’s leader — for 38 years. He only gave up power in 2023, handing it to his own son.

Instead of repair, repression took root. People wanted stability. Autocracy filled the vacuum. Today, the government that claims credit for ending the Khmer Rouge has consolidated power through fear, surveillance, censorship and assassinations.

America and the world must heed this cautionary tale.

When trauma is not acknowledged, let alone addressed, the potential for healing can mutate into corruption: hoarding control or power to manage fear or insecurity. It can look like censorship: silencing discomfort rather than addressing its root. It can creep in as authoritarianism: offering safety through control rather than connection.

But this isn’t a fait accompli.

Our brain is flexible, as is our body. With support, trauma can transform into care, creativity and collective strength. Research from trauma experts Judith Herman and Peter A. Levine emphasizes that healing requires safety (physiological and relational), narrative integration (being able to make sense of the experience) and connection and agency (being seen, believed and empowered). These can turn chronic stress into lasting resilience, growth and cohesion — the kind that nourish both relationships and democracies.

The United States today is not Cambodia in 1975. But it is a nation increasingly shaped by unaddressed harm — slavery, displacement, economic exploitation, White supremacy, political violence. The January 6 insurrection and the pardoning of its perpetrators. School shootings. Militarized policing. Our nervous system as a nation is frayed. And just as individuals can become dysregulated, so can communities and institutions. When a society’s collective trauma isn’t acknowledged, it builds systems designed to avoid discomfort, not confront it. It rewards suppression over reflection. It mistakes order for peace.

This is why trauma-informed approaches aren’t just about personal healing — they’re civic and institutional imperatives. Because, like in Cambodia, many Americans seeking stability, a relief from struggle, are refusing to believe the malicious intentions of an autocratic strongman. People are being lied to, manipulated to hope that giving up their freedom and rights and bowing to the pressure of a leader unmoored from laws and the Constitution will keep them safe.

In the U.S. today, the ruling party is trying to censor and rewrite the country’s history to ignore the more difficult parts of what we’ve been through. It is consolidating power through fear, surveillance and systemic silencing — arresting people for protesting, threatening and punishing media that report independently, vilifying students and educators, ripping funds away from institutions that don’t agree with its ideologies.

Is Washington taking cues from Phnom Penh, or is it the other way around? On April 17 in Cambodia, authorities denied the request of a political opposition party to hold a memorial for Khmer Rouge victims, citing issues of “public order,” according to Agence France Press reporter Suy Se.

Americans and the world, take note: Cambodia is functioning but not flourishing. Still, there are people who brave threats to protest systemic abuses of power. And defiance is not only public, it’s deeply personal. Loving oneself and others in the aftermath of collective violence is, in its own way, an act of resistance. Cambodians are full of love. I know this well. It was in Phnom Penh — through the quiet, unwavering love of a Cambodian man I once called home — that I began to heal from my own childhood trauma.

Here in the U.S., this era of American authoritarianism grew out of unhealed trauma. It crept in with hyper-capitalism that disguises extraction as empowerment and markets disconnection as freedom, as well as the extremist ideologies of leaders who manipulate people with fear and division. We know this now, right? If a nation doesn’t metabolize its pain, that pain finds new forms. What’s repressed gets recycled.

When a nation doesn’t metabolize its pain, that pain finds new forms. What’s repressed gets recycled.

Like the covid-19 pandemic, this tyrannical virus will eventually ease if people unite against the threat, if not in years, then in decades. And when it does, Americans will be anxious to just get back to the way we were. But doing so leaves the seeds of pain ready to be reaped again. Disrupting harm is not enough. We have to intentionally build the conditions for repair. These include embodied safety and dignity, accountability and justice.

This work requires the freedom to feel — grief, rage, hope, joy — and an awareness of how trauma lives in our bodies and affects our relationships. We need truth-telling, not just about personal pain, but about deeper harms built into our systems. We need trauma-informed policies and practices in our workplaces, schools, hospitals, prisons, media and legislatures. We need civic education that teaches not only rights and responsibilities, but also how historical injustices have shaped the present. And we need narrative repair circles — whether in city councils, church basements or town halls — to bear witness, to rebuild trust and to imagine new futures together.

Fifty years on, Cambodia stands as both a testament to human endurance and a mirror for nations like the United States, where the work of collective healing is urgently needed yet still unfamiliar to many. We are not powerless in this moment of need. Every conversation, every curriculum, every vote, every act of compassion is a thread in the fabric of repair.

Action guide: How to take this story personally

This essay isn’t just about Cambodia. It’s about what happens when any society — or person — understandably mistakes survival for healing, and silence for peace.

Use these key points and reflection questions to connect the lessons to your own life and strengthen your capacity for grounded, lasting change.

Key takeaways

Unprocessed pain doesn’t disappear — it evolves. Trauma that’s ignored often re-emerges as harm to self or others.

Stability is not the same as healing. Without justice, accountability and repair, cycles of harm continue beneath the surface.

Authoritarianism thrives on fear, disconnection and exhaustion. It takes root when people are too overwhelmed to resist — or too afraid to imagine something better.

Healing is not passive. It requires truth-telling, rebuilding trust and reconnecting to our bodies, relationships and histories.

Resilience is a resource we build — not by toughing it out, but by feeling safely, connecting deeply and choosing differently.

You are not powerless. Every act of reflection, compassion, or courage — no matter how small — helps interrupt the cycle and repair what’s frayed.

Questions for personal reflection

On cycles of harm and healing:

Where in my life have I mistaken endurance or numbing for healing?

Have I accepted harmful behavior or systems because I was afraid or exhausted?

What cycles of silence, judgment or self-protection have I inherited — and how might I begin to shift them?

On grounding and resilience:

What helps me feel more steady when I’m overwhelmed? A breath? A walk? A hand over my heart?

Who or what helps me remember who I am when I forget?

What qualities have helped me get through hard things in the past? Can I name them with pride?

On strength and truth:

Where in my life have I practiced strength by choosing truth — even when it was uncomfortable?

What’s one small truth I’ve been afraid to speak — to myself or someone else?

How can I offer honesty or care today without needing to fix everything?

On collective repair:

What kind of world do I want to help create?

What’s one small thing I could do to make someone else feel safe, seen, or supported?

How can I support spaces — at work, at home, in my community — that allow for honesty, grief, and growth?

Gentle reminders

You don’t have to feel everything all at once. Ground yourself first. A slow breath. Feet on the floor. One hand on your chest.

Healing is not linear. And you’re not late to it. You’re here now.

You are not alone. There are people doing this work alongside you — quietly, steadily, every day.

A little background

I’m Kate Woodsome — a trauma-democracy scholar, strategic advisor and resilience coach rewiring the connections between democracy, information and wellbeing. A Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and Georgetown University fellow, I help people uncover and understand the underlying dynamics of trauma and stress that shape how we communicate, make decisions and relate to one another. By making the invisible visible, my work aims to empower individuals and institutions to shift harmful patterns, restore trust and move through complexity with clarity and care.

Invisible Threads is the independent platform where I tell stories, teach and create tools to transform trauma into resilience — and to help people reconnect with themselves, each other and our democracy.

This mission depends on reader support. If it resonates, please subscribe, share or consider becoming a paid member. You make it possible.

To see if it’s worth it, here’s a few more articles from the archives:

Got grit? What about resilience?

White-knuckling is not a long-term strategy.

A journalist’s guide to staying grounded at protests

How to show up without losing yourself in the noise.

The Voice of America needs us to hope

Hope is not a wish. It's an action.

Step by step, together. — Kate

Monumental essay. Vitally important. Thank you Kate Woodsome.

Excellent. It's interesting to me how many of us expats with our own unhealed trauma--found ourselves living and working in Cambodia during a time when we believed we could make a difference. For me, subsequent years have been all about healing. I love how you are weaving historical and personal stories to give readers a roadmap to their own healing process.